Wonder Drug

When it comes to housing policy for family-friendly cities, there are few easy answers. But there is at least one, popular in Europe. In fact, it is one of the reasons some of the continent’s communities are among the best in the world for raising children and aging in place.

Architects call it the “points access block,” or “single stair entry building.” Lay people like me prefer the less precise, “stacked flat.”*

The stacked flat comes close to a miracle cure for some of Seattle’s ills.

The Malady

For cities like ours, with unrelenting demand to live here and unimaginative politics, it is hard to build housing fast enough to keep prices reasonable. It’s well understood that we need increases in capacity.

But when we do build, we tend to cram housing into small places and make it so developers really only make money off of tiny, drab units with windows on one side, or extremely vertical townhomes, which are lousy for seniors and anyone living with disabilities.

To top it off, these types of buildings too often turn their communities into concrete jungles. Neighborhoods become less livable, and they amplify urban heat island effects in our increasingly hot summers.

All this shores up support for housing-reluctant politics. After all, if we wreck neighborhoods when we build new housing, we will naturally undermine the political support needed to sustain housing growth.

The Stacked Flat

Enter the humble stacked flat.

The stacked flat gives us much more housing for the building footprint, because it wastes far less space. It does this so well, in fact, that we can vastly increase our capacity to produce homes, make more of them family sized, and do a much better job than we are today when it comes to green space and trees.

That seems too good to be true, but the example below will explain how it works.

One of the US’ foremost experts and evangelists on this kind of building is Mike Eliason, who lives in Seattle and runs Larch Lab, an architecture, planning and advocacy firm.

On Twitter, Mike recently walked through an example that shows how stacked flats can get us more housing capacity and preserve more greenspace at the same time.

What follows is lifted (with permission) from Mike’s twitter feed. I quote liberally, paraphrase in my own voice, and simplify technical terms. Full credit for the good parts go to him. The mistakes are mine.

The Status Quo: Worst of Both Worlds

Eliason starts with a typical block in a Seattle Neighborhood. It is 250' x 400,' or 100,000 square feet (2.3 acres). The zoning is multifamily, and is loaded with a mashup of everything from single family homes, to townhomes and four story apartment buildings.

Notice that there is very little open space.

In this Seattle block, the townhomes are the biggest offenders. A ton of their footprint is set aside for stairs. Along with their driveways, they eat up most of the lot, leaving little left for trees or other natural life.

This is in part because Seattle’s rules allow buildings with too big of a footprint for their height and property size. And, the way the rules work, these big buildings require a hotel-style hallway down the middle, with stairway exits on each end.

And that screws things up, a lot.

The fact that homes sit on one side of a hallway means that, except for end units, all those people have light and air on only one side of their living space.

The hallways sacrifice gobs of the building to dead space, which means the building footprint is far too big for the amount of living space it actually creates. The second set of stairs similarly wastes more space.

With two exits, the fire code allows developers to put the front doors of the apartments farther away from the exit stairs than it does when there is only one stairway.

This creates an unfortunate incentive. Since they can have more doors, developers end up splitting the space into many more little units per square foot. Small units are fine, and needed. But since small units are usually more profitable in this setup, they are almost all that gets built. Families don’t fit.

And a lot of space ends up dedicated to kitchens, since a building full of studios and one bedrooms means almost every bedroom has its own kitchen.

Condos’ Paradox: Less Building = More Housing and More Trees

The inverse happens if the rules shrink the building size to the right amount where you end up with a few flats per floor and a single point of entry.

The benefits are staggering:

Because this kind of building eliminates so much waste (no big hallway or secondary exit), much more of the building is used for living in. A smaller building can actually generate more living space.

With a single exit, the fire code limits the number of units you can have–because a front door can only be so many feet from the exit stairs. This caps the number of units the developer can create per floor. Since developers tend to max out their allowable square footage, but have a limited number of doors/units, they end up building larger, family-sized units.

More multi-bedroom units means fewer kitchens per bedroom, since one kitchen will now share several bedrooms. This once again means a more efficient use of building space.

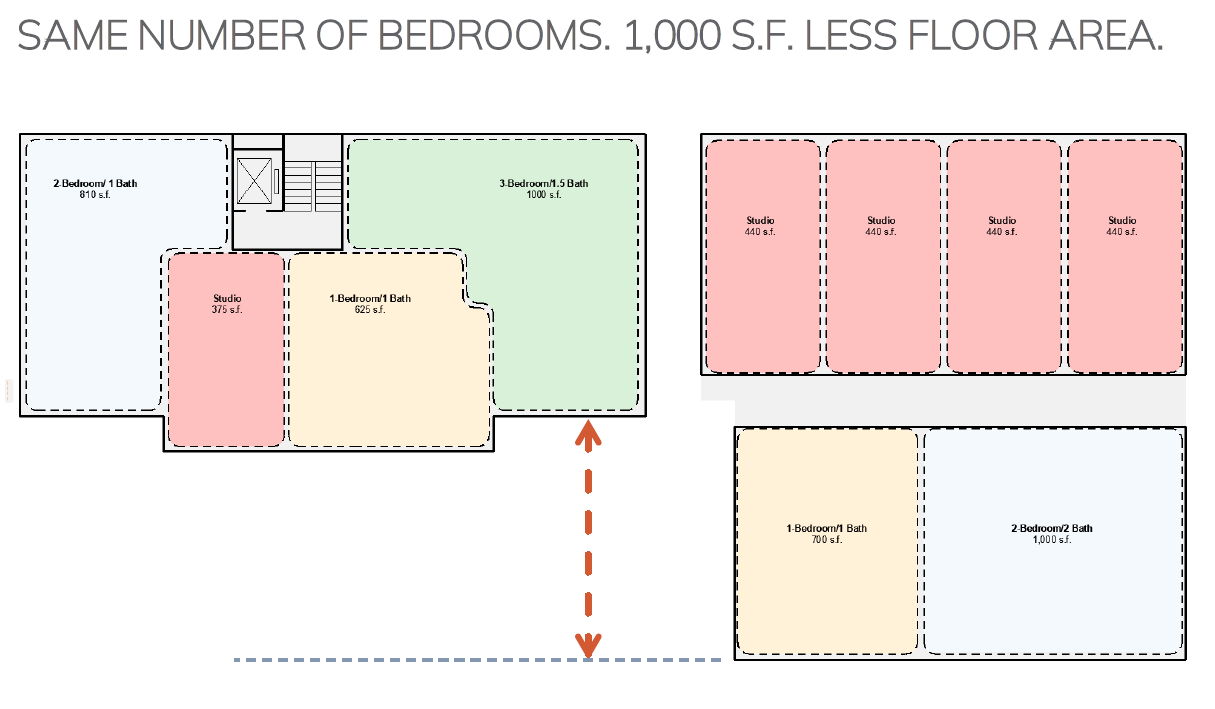

Eliason shows an example of how you can have the same amount of sleeping space but a smaller building.

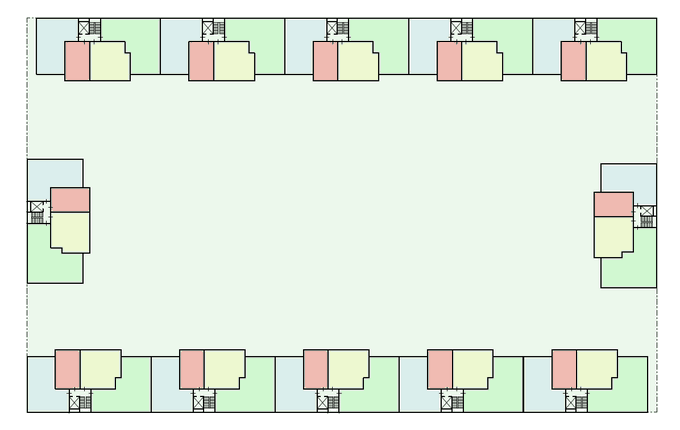

He then shows what it would look like to take this building and do as the Europeans do, but on his original sample Seattle block.

He places 12 buildings around the perimeter. This makes space for 25 residents (bedrooms) per 4-story building. That’s 300 residents, or 130 people per acre. No need for skyscrapers or carbon intensive steel and concrete here.

This many families can easily support great public services like schools and frequent transit, as well as walkable neighborhoods with a variety of shops. And the mix of single level small and larger units allows for all stages of life–an intergenerational community.

If you go up to 6 stories, it’s close to 200 people per acre.

(In Seattle, we are currently at about 29 people per acre, assuming half our land area goes to roads and other nonresidential uses).

What is particularly powerful is that you can create all that housing capacity and still leave 65% of the site for open space or trees, or parking if traffic is your jam.

Nirvana Has Left the Building

Now compare Eliason’s example with the sample block in Seattle.

The Seattle version takes up more of the land space, with similar building height, but produces far less living space. It has only 130 bedrooms, or 56 bedrooms per acre–way less than half of the four story stacked flats example. Most units are not for families either, except the townhomes, which are lousy for aging in place.

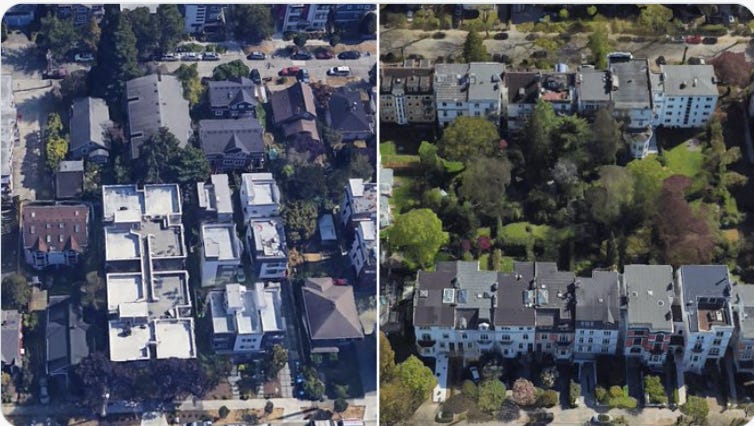

Eliason compares the Seattle block to a built out example from Hamburg, Germany.

German (building) efficiency is beautiful

In the Seattle example, green space is covered over, and units look directly into one another, only 15’ away. Eliason’s example and the Hamburg picture both offer far more privacy and natural beauty.

All that saved space adds up in a hurry. The total building square footage Mike laid out above is about 144,000 square feet for 300 residents. Compare that to the square footage for the Seattle block with 130 residents. It’s almost three times as much building—with tons of that going to wasted hallways, stairwells, and extra kitchens.

Athens or Spartan?

Eliason makes one last note–and pulls up an example of a new Seattle development in Greenwood. It’s called “Hemlock,” which may frighten fans of Socrates, but clearly targets fans of trees.

This Hemlock place might leave them weak in the knees, because there is nearly no space for outdoor life.

This block is a bit smaller than Eliason’s earlier Seattle sample, and it does manage to fit in 285 residents. But it takes 6 floors to do so, with part of the bottom floor allocated to retail.

This building has roughly 350,000 square feet dedicated to residential. And it has room for fewer residents than the 144,000 square feet example from Eliason above. And in the Seattle building, the units are generally smaller.

Besides destorying outdoor open space, wasted building space is expensive and bad for the environment, because of materials and heating.

I’d rather have cheaper, environmentally friendly, nicer housing, with more open space and trees in a more livable city. I suspect you would too.

Time to tweak our code and time for me to stop trying to find puns to punctuate wonky writing.

*Technically you can have dual stair stacked flats, but for the rest of this little discussion, I’ll be using stacked flats to refer to buildings with only one staircase.

**Okay, I know it’s not a perfect silver bullet. The way our condo rules are written (related to shared building and property ownership), they tend to command a lower sales price per square foot when compared to townhomes, though as I understand it, the rents can be similar. This offsets some of the economic gains from the building footprint efficiency. However, this is given the current regulatory setup and all the incentives it creates. A pretty simple tweak to our code to limit lot coverage to, say 40%, will accomplish the reasonable public good of protecting trees and open space. And it will tilt the incentives to build such buildings in the right direction.